eBPF and Perfetto UI proved me wrong

by Kunshan Wang

This blog post is about an experience of debugging MMTk using a tracing and visualisation tool based on eBPF and Perfetto UI. During debugging, I tried to guess what went wrong for many times, but the tool showed what actually happened and proved me wrong each time.

The anomaly

I made a pull request for MMTk-core. It sped up all benchmarks in the

DaCapo Benchmarks suite, except the jython benchmark which became 3x

slower in stop-the-world (STW) time (i.e. time spent doing

garbage collection).

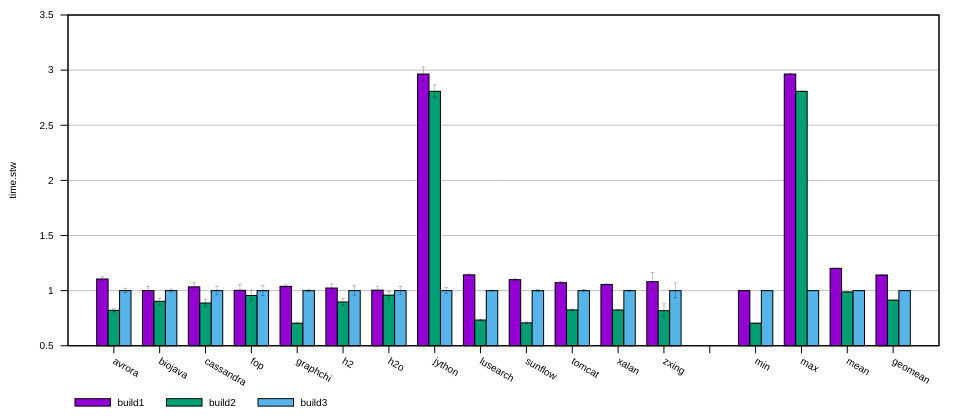

In the following plot, build3 is the baseline revision, build1 is an

intermediate commit, and build2 contains my final change. The time is

normalised to build3 for each benchmark.

I could conclude that the jython benchmark had some abnormal behaviour and the

overall result (build2 in geomean) was still speeding up. But the 3x

slow-down was too significant to overlook. I decided to investigate.

eBPF-based tracing and visualisation

Strangely, the slow-down was only observable on two of the testing machines in

our laboratory. When I re-ran the jython benchmark with build1, build2

and build3 on my laptop, their stop-the-world (STW) times were similar. They

were either equally good or equally bad. I guessed they were equally bad. I

inferred that the problem was non-deterministic. It may be triggered under some

unknown conditions.

The slow-down was in the STW time, which meant some GC activities became slower. But how would I know which GC activity was slow?

At that time, my colleagues were developing a eBPF-based tracing tool which can record the duration of each work packet during a GC, and visualise them on a timeline. Its overhead when not used was so low that we can leave the trace points in the code in release builds, and active them whenever we want to measure something. I thought it was the perfect tool for my task. Although the tool was still being developed, I asked my colleagues for a copy and gave it a try anyway.

The tool included a patch to the MMTk Core source code which inserted USDT (user

statically-defined tracing) tracepoints at important places. They were compiled

as NOP instructions, but could be patched at run time to execute custom code.

I used the bpftrace command line utility to activate those tracepoints to

record the start and the end of each work packet, then used a script to format

the output into a JSON format which was then sent to Perfetto UI. Perfetto UI

showed what happened during a GC in a timeline.

Actually, I observed two different timeline patterns from different GCs when

running the jython benchmark.

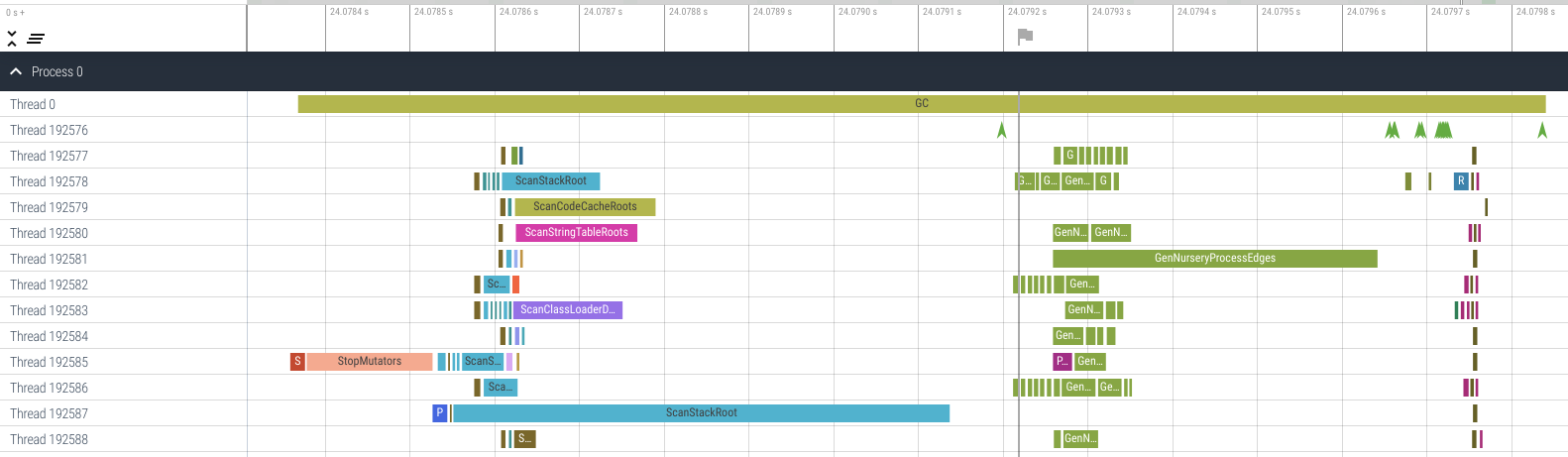

The first pattern (I called it the ‘kind 1’ GC) looked like this:

This was a minor GC in a generational GC algorithm, and it was quite a typical one.

The green arrows in Thread 192576 marked the start of each stage.

- The

Preparestage happened before the green arrow near the ‘24.0792 s’ mark, during which there were many work packets namedScanXxxxRoot(s). - The

Closurestage happened between that green arrow and the next green arrow after the ‘24.0796 s’ mark, during which there were many greenGenNurseryProcessEdgeswork packets. - Then there were some short intermediate stages, such as

FinalRefClosurewhich handled finalization. - The

Releasestage happened near the end of the GC between the ‘24.0797 s’ and the ‘24.0798 s’ marks, where each worker executed some clean-up job.

Since a minor GC does not trace much objects (it only traces the nursery), the

Closure stage did not took much time. A ‘kind 1’ GC typically takes only

about 1 ms, despite the ScanStackRoot work packet in Thread 192587 and the

GenNurseryProcessEdges packet in Thread 192581 being a bit too big due to an

unrelated load-imbalance problem.

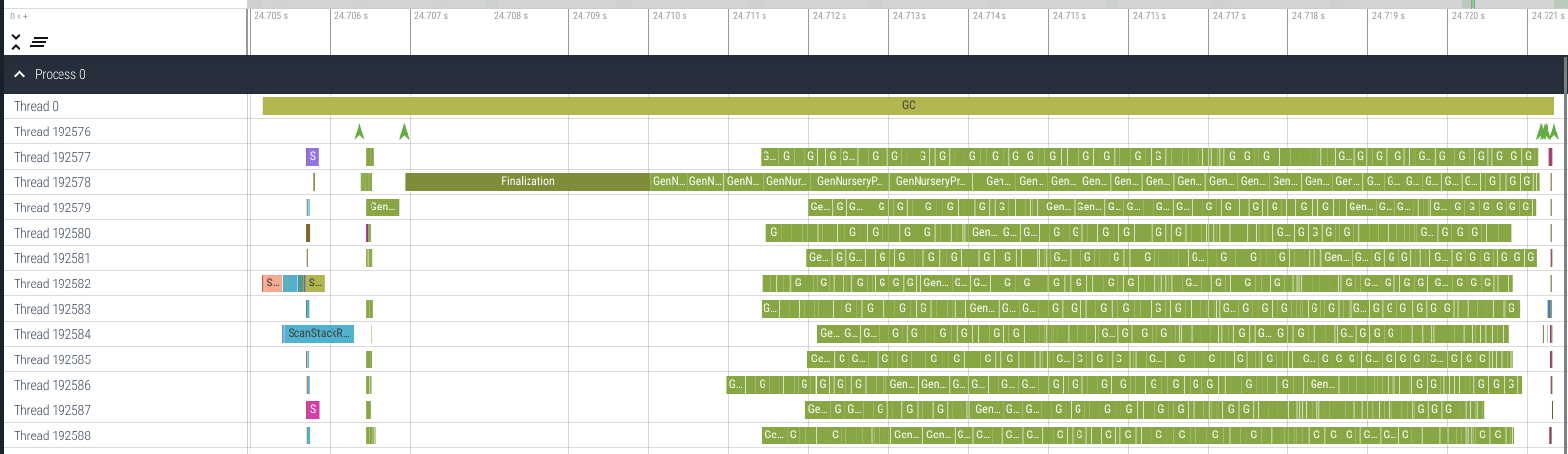

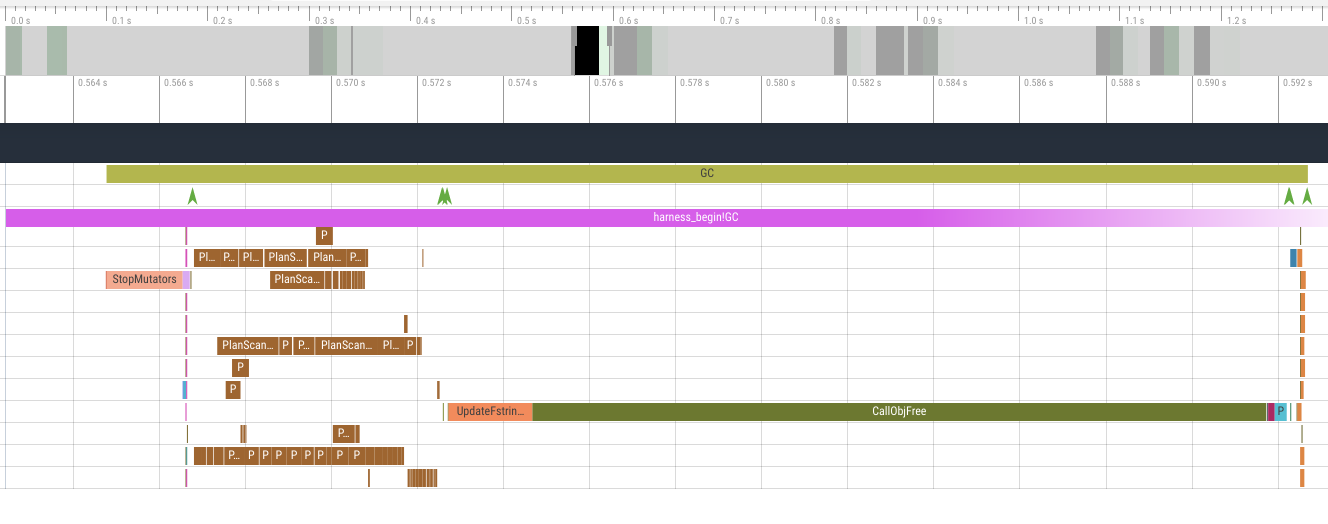

The second pattern (I called it the ‘kind 2’ GC) looked like this:

This was also a minor (nursery) GC, too, seen form packet name

GenNurseryProcessEdges. The Prepare stage and the Closure stage are

similar to the ‘kind 1’. (Please note the horizontal scale of the timeline.

The Prepare and the Closure stages were in the far left of this plot, before

the Finalization packet.) What was interesting was the FinalRefClosure

stage where finalization were done. After the Finalization packet, lots of

GenNurseryProcessEdges work packets were executed. It was obvious that

finalization resurrected many objects. A ‘kind 2’ GC is significantly longer

than a ‘kind 1’ GC. It may take more than 15 ms to execute.

Given that finalization is non-deterministic, we might infer that the slow-down was caused by an excessive amount of finalization due to non-deterministic execution. Problem solved…, or was it? I still needed to verify.

Printing out the GC times

I printed out the GC time of each GC in jython when running on a test machine

in the lab.

With 1500M heap size, the GC time (i.e. STW time) of the original code

(build3) and my modification (build2) were:

- Before: 2,2,1,8,1,2,9ms

- After: 1,21,1,10,1,20,9ms

So the GCs that took 21, 10, 20 and 9 ms should be doing finalization, right?

I ran it on another test machine (with identical hardware) with 1500M heap, too:

- Before: 2,1,1,11,1,3,8ms

- After: 2,27,1,9,2,25,8ms

The results were similar between two machines. I then tried to reduce the heap size.

When I reduce the heap size to 500M:

- Before: 1,1,1,1,1,2,2,1,1,5,9,2,2,1,2,1,1,2,1,2,1,5,8,4

- After: 1,1,1,1,1,30,1,1,1,4,8,1,1,1,1,1,1,27,1,1,1,3,8,4

When I reduce the heap size to 250M:

- Before: 1,1,2,2,2,1,1,2,1,1,2,1,3,1,2,2,1,1,1,1,2,4,5,6,4,1,1,2,1,1,2,1,1,1,2,2,1,2,2,2,2,2,1,1,1,1,1,2,1,1,4,7,5,4,2,2,

- After: 1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,2,1,29,1,1,1,2,1,1,1,1,4,6,6,1,2,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,2,25,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,4,5,5,4,1,1,

If the slow-down were caused by excessive finalization, I would expect one build

to have more GCs that had more than 15 ms of STW time. But it was not the case.

Two builds had the same number of GCs, and the GC time of each pair of

corresponding GCs were similar, too, except two pairs. No matter how large the

heap size was, there were always exactly two GCs that took more than 20 ms in

the ‘After’ case (i.e. build2, the build with my PR applied). For other GCs,

most of them took 1 ms and I assumed they were the ‘kind 1’ GCs; some of them

took 5 ms to 10 ms and I guessed they were the ‘kind 2’ GCs.

So the two 20+ ms GCs were interesting. What happened during them? Were they slow because of finalization, too?

I re-ran the test at 250M heap size on my laptop. Strange things happened.

- Before: 1,1,1,1,1,2,1,1,1,1,1,2,1,2,2,1,2,2,2,2,1,2,1,5,7,7,6,1,2,1,1,1,2,1,1,1,2,1,2,2,2,1,1,2,2,2,1,2,2,2,1,1,2,2,2,1,5,7,6,5,1,2,2,

- After: 2,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,2,1,1,1,2,2,2,1,2,2,2,2,1,1,1,7,8,7,5,1,1,2,1,1,1,1,1,1,2,2,1,1,1,2,1,2,2,2,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,4,6,6,6,4,1,1,

The mysterious 20 ms GCs vanished!

This meant those 20 ms GCs were definitely not ‘kind 2’ GCs because otherwise I would have observed them on my laptop.

This also meant I could not capture those mysterious 20 ms GCs on my laptop using eBPF tracing. I could only capture them on the lab machines.

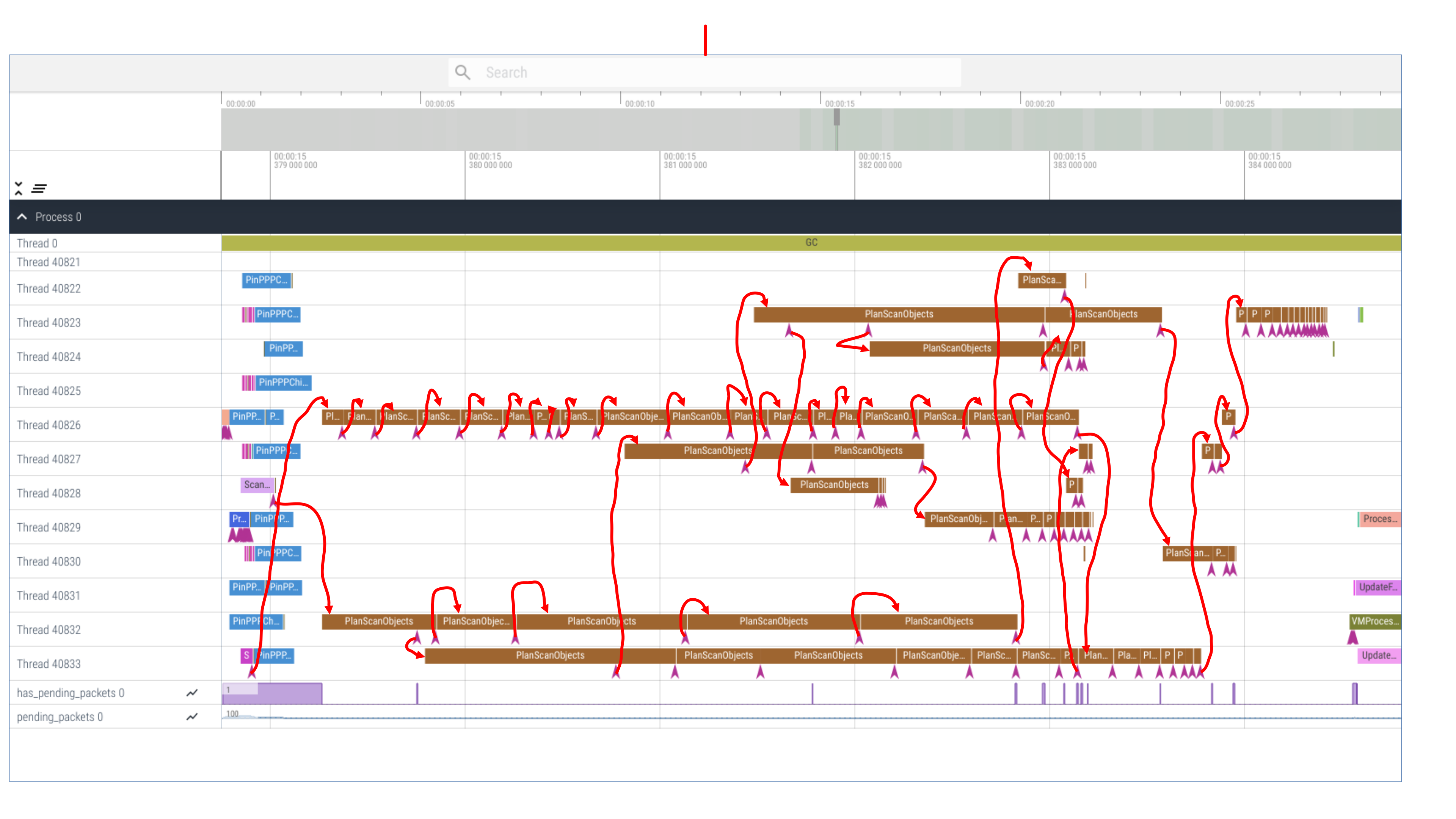

Manual tracing

Since I could not use eBPF tracing on the lab machine due to lack of root access, I manually instrumented the code to log the starts and ends of each work packets. I printed the log in the same format as the output of the eBPF tool, used the same script to process the log into the JSON format, and fed the JSON into Perfetto UI. Then a nice timeline came out. (And you can try it by your self. Load this log file into https://www.ui.perfetto.dev/ and browse the timeline interactively.)

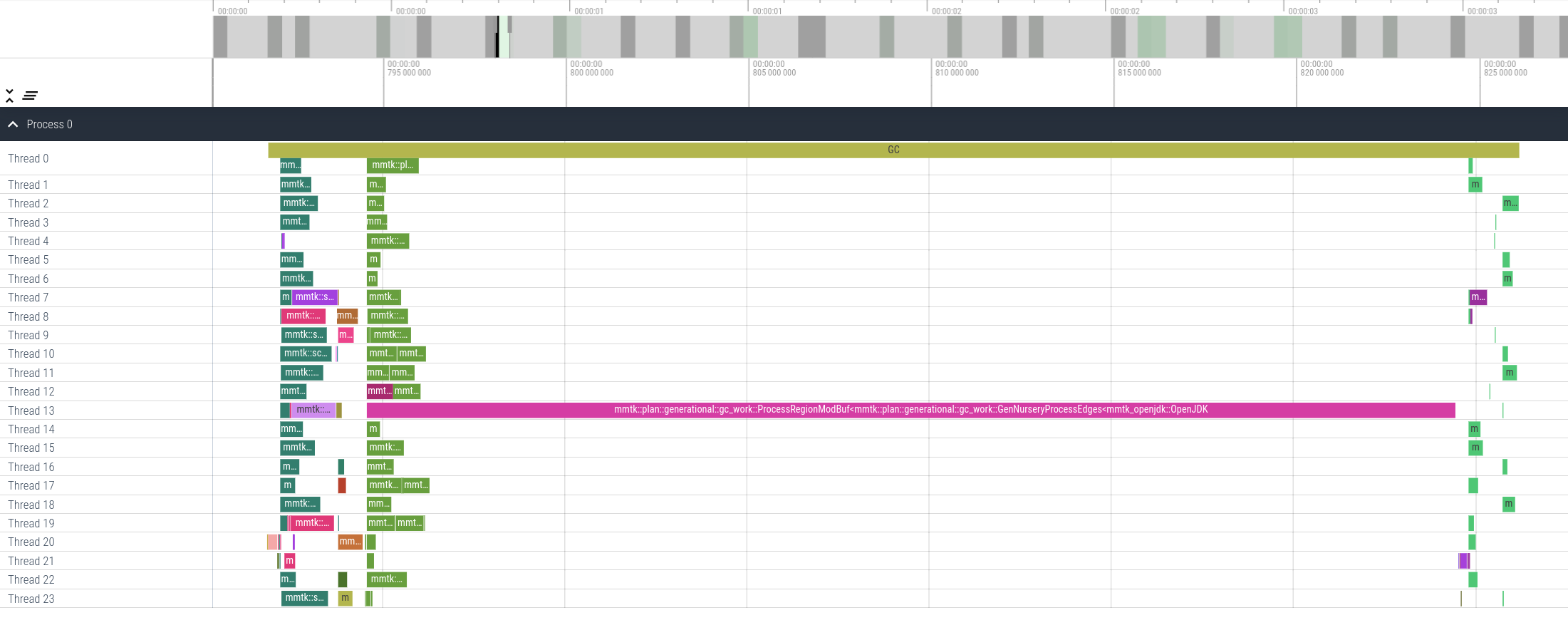

And that was a strange timeline, too. Why was the ProcessRegionModBuf work

packet so large? The purpose of the ProcessRegionModBuf work packet is

handling the write barriers for bulk accesses of arrays (such as

System.arraycopy() in Java) between the last GC and this GC.

There might be two possibilities:

- The

jythonbenchmark did callSystem.arraycopy()on a very large array, therefore the work packet should exist in order to process the write barrier. However, it did not appear in the ‘Before’ build (build3) due to a bug. - The

jythonbenchmark did not copy large arrays at all, but a bug (probably introduced or triggered by my PR) caused the write barrier to erroneously record an access to a large array while it did not, resulting in an abnormally largeProcessRegionModBufwork packet.

So which one was true?

Hacking the write barriers

I added a log at the place where a ProcessRegionModBuf work packet is created

in order to see the sizes of the ProcessRegionModBuf work packets.

When running on the lab machines,

- in the ‘before’ build, all

ProcessRegionModBufwork packets had lengths of 0; - in the ‘after’ build,

ProcessRegionModBufcame in all different sizes.

When running on my laptop, all ProcessRegionModBuf work packets had lengths

of 0.

But it does not make sense to copy zero elements using System.arraycopy()!

Then I had reasons to believe that there was a bug in the write barrier code so that in the ‘before’ build, the write barrier failed to record any accessed array regions, making the GC erroneously faster than it should have been. In the ‘after’ build, the bug was not triggered, so the accessed array regions were recorded by write barriers as usual, resulting in a longer but actually normal STW time. In other words, it was not my PR that made the STW time longer, but the STW time had been shorter than it should have been.

One of my colleagues reminded me that there was an un-merged commit that fixes a bug in the write barrier code in the MMTK-OpenJDK binding. It was intended to fix an unrelated bug, but it was still worth giving it a try.

I cherry-picked that commit, and… Voila! It fixed the bug! The ‘before’ build then exhibited the two 20+ ms GCs, just like the ‘after’ build.

- Before: 1,2,2,1,1,29,1,1,2,5,8,2,1,1,1,2,1,29,1,1,1,4,9,3,

Conclusion

At this point, we could draw the conclusion. The STW time for the jython

benchmark should have been 3x longer. However, due to the bug fixed by this

commit, the barrier did not record the bulk accesses to arrays

properly, and therefore did less things than it should have done. When I was

running the DaCapo benchmarks at the beginning of this blog post, I set the heap

size too large (1500M). With such a large heap size, GC was only triggered a

few times, and the proportion of write barrier handling became more significant

in STW time. Therefore the STW time for jython was only 1/3 of the normal

time due to the missing write barrier handling.

However, my PR changed the behaviour in some way, and the bug was somehow not

triggered when running on the test machines in the lab. And the sub-optimal

implementation of the ProcessRegionModBuf work packet stuffed all the array

slices delivered from barriers into one single vector, making it impossible to

parallelise. It gave us a false impression that my PR made the jython

benchmark 3x slower on the lab machines.

And due to non-determinism, the bug was still reproducible on my laptop with my PR applied. That was why I saw the 3x slow-down on the lab machines but not on my laptop.

What did I learn?

There is a saying that ‘One can not optimise things that one can not measure’. It

is very true. I can hypothesise what caused the performance problem, but I can

never be sure unless I verify it with experiment. In this example, I first

thought the slow-down was just some random behaviour of the jython benchmark.

I then thought the slow-down was due to excessive finalization. But experiments

showed that the actual cause was a bug in the write barrier.

And the visualisation tool is a very useful one. It first showed me that some

GCs took longer time due to finalisation, and it then showed me that there were

even longer GCs due to buggy and sub-optimal write barrier handling. It is such

a useful tool because with the timeline in front of me, I no longer need to

guess what slowed things down. I just look at the timeline, and the work packet

that becomes the bottleneck will stand out of the crowd. Since the eBPF-based

tracing and visualisation tool was created, I have been using it to debug many

performance issues in GC, including the execution of obj_free, various weak

table processing tasks, and the load-balancing problems in the MMTk-Ruby

binding.

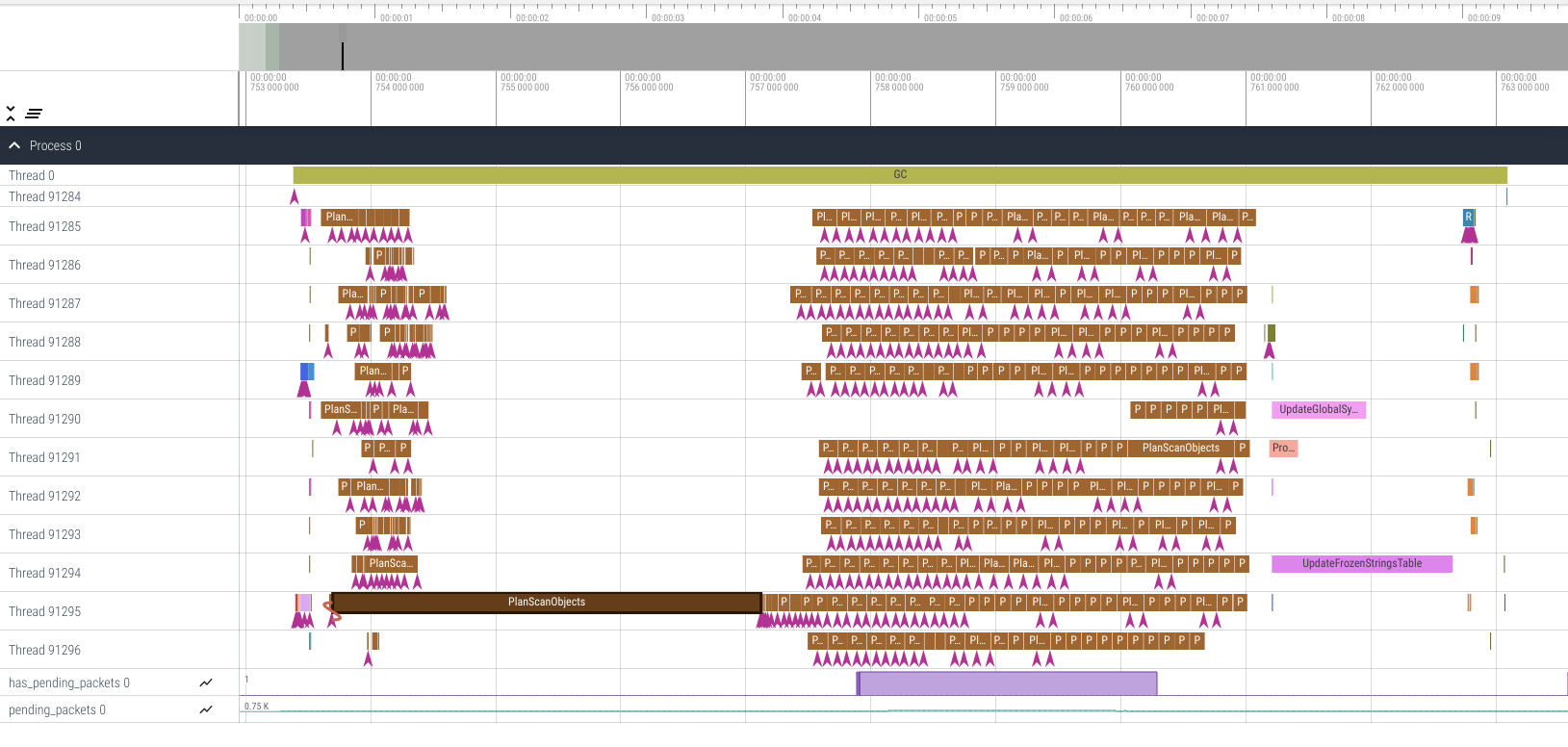

For example, when I saw the following timeline, I knew the handling of

obj_free was the bottleneck.

When I saw the following timeline (with manual annotation of which work packet created which), I knew the load balancing of the transitive closure stage needed to be improved.

And when I saw the following timeline, I knew the general load balancing was improved, but some objects took significantly longer to scan than other objects, and I should focus on those objects because they were the bottleneck.

The tool

I thank Claire Huang, Zixian Cai, and Prof. Steve Blackburn for creating such a useful tool.

The tool is now publicly available. The code has been merged into the master branch of mmtk-core. Related tools and documentation can be found in this directory.

The paper that describes this work is freely available online under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, and will be presented in the MPLR 2023 conference.

tags: mmtk - ebpf - perfetto