OSPP'2023: The good, the bad, and the ugly

by Kunshan Wang

TL;DR: Last year, the MMTk project participated in the Open-Source Promotion Plan (OSPP). We mentored two students and they completed two student projects, which was cheering. But the OSPP’2023 event itself was organised in a way I found frustrating, and even hostile to the free software community. Meanwhile, I realised that there were toxic people lurking in the community, which was worrying.

WARNING: Contains harsh words. Viewer discretion is advised.

The Open-Source Promotion Plan (OSPP)

The United States started a trade war against China several years ago, and my former employer was on the ‘Entity List’. Depending on your political stance, you may support one side or the other. But the trade war raised a real concern for every company about their software supply chain. If your company suddenly appears on the Entity List of some country (including but not limited to the US), your favourite software may immediately become unavailable. For instance, MATLAB is no longer available to the Harbin Institute of Technology.

This is where free software (a.k.a. free open-source software, or FOSS for short) comes into play. What will you fear for if you have the complete source code (and probably the entire revision history) in your hard drive (not in the ‘cloud’), and the contributors have given you a perpetual, worldwide, non-exclusive, no-charge, royalty-free, irrevocable license to run, copy, distribute, study, change and improve the software? Free software (and free hardware, too) is the ultimate answer to protectionism. Since the trade war started, Chinese companies and the government started to embrace free software more than ever. Some government agencies even switched to domestic GNU/Linux distributions as their primary working environments for average workers.

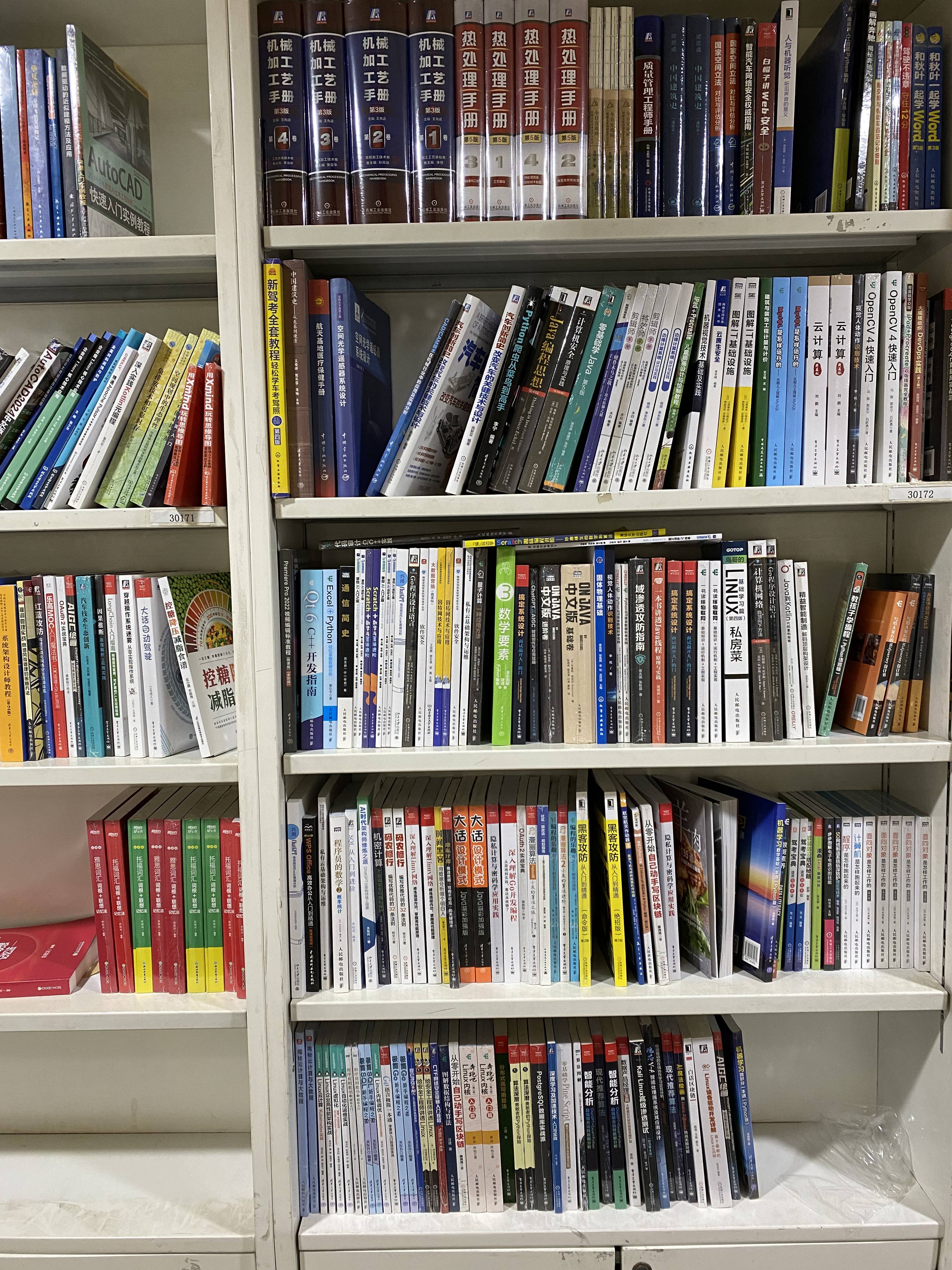

Here is a photo taken from the computer science section in a Xinhua Book Store in Beijing. The book store is currently under refurbishment, so only a small fraction of books are displayed. Even if you don’t read Chinese, you can still recognise books about open-source technologies such as Linux, Apache Pulsar, Kotlin, Python, Java, OpenCV, Qt 6, Scratch, Go, R, OAuth2 and PostgreSQL. This means free software is no longer a niche technology in China, but a technology on popular demand.

The Open Source Promotion Plan (OSPP) is an event organised by the Institute of Software, China Academy of Science (ISCAS). According to OSPP’s official website, it is an explicit goal of OSPP to ‘build the open source software supply chain together’. Similar to Google Summer of Code (GSoC), OSPP funds students (not limited to Chinese nationals) to participate in free software projects for three months (from July to September) in Summer.

- For students, such events give them motivations to make contribution, for the love of FOSS or just some extra cash.

- For FOSS projects, such events give them an opportunity to attract contributors, and also get some low-priority tasks done while main contributors are busy with high-priority issues.

- For the organiser, ISCAS, and the Chinese government backing it, this event encourages more people to participate in FOSS development, which will eventually yield a stronger free software community and help both Chinese users and FOSS users worldwide to counter protectionism.

That is a win-win-win situation.

The MMTk project participated in the OSPP in 2023, and I was the project representative of MMTk. Two students worked with MMTk, and I mentored one of them. The good thing is, both students finished their tasks, and we are grateful to ISCAS for organising such an awesome event, and to the students for their contributions. However, the experience of participating in OSPP is not 100% pleasant, and I’ll elaborate.

The good

I have always been a FOSS enthusiast. In late 2000s and early 2010s, I attended many off-line activities related to FOSS in Beijing (because I studied in Beijing). That included several student societies in my university, the Software Freedom Day, activities from local user groups such as the Beijing Linux User Group, the Beijing GNOME User Group, etc. Then I went to Australia for my PhD, where I enjoyed exciting talks and pizzas with the Canberra Linux User Group. After I returned to China, I didn’t find much chance to get together with local communities due to work pressure and COVID19. I missed the days when FOSS lovers (including both Chinese and foreigners working in Beijing) get together once a month, bringing laptops, and coding for fun.

I heard about OSPP in late 2022, and thought MMTk should participate in the next year in order to let more people know about MMTk, and probably let more people know how awesome the Australian National University (ANU) is, too. I couldn’t wait telling FOSS lovers that we are doing interesting researches on memory management and working on open-source projects with collaborators from many different countries. And we did. We applied for participation in OSPP’2023, and we were accepted.

Meeting the organisers

In early 2023, I met an OSPP organiser in an off-line meeting, and I was very excited to know that they were working hard to promote free software. The organiser told me that OSPP organisers had visited several universities in different cities in China in order to get more students know about OSPP and free software in general. The organiser also told me that although free software was already very popular among top-tier universities in Beijing, it was far from true in lower-tier universities in smaller cities. I appreciated their efforts. It takes time and energy to get people aware of free software, and it is harder for them to understand the spirit of software freedom, but it is worth trying.

During the whole OSPP’2023 event, the organisers helped us with the process of registration as well as overcoming errors of their poorly engineered website (I’ll elaborate in the next section). They tried their best keeping the event running.

The organisers also invited participating communities to submit introduction videos so that they can help promoting their projects by publishing the videos on behalf of the communities. Professor Steve Blackburn, the leader of the MMTk project, gladly made a video to provide a brief introduction to MMTk. He even recorded it several times to correct minor mistakes. I created Chinese subtitle for it and sent it to the OSPP organisers.

The students

The event went on well. We posted two student projects, one for migrating our JikesRVM binding to the new weak reference processing API, and another for supporting ARMv8. Several students expressed their interests in our Zulip channel, and some even asked for easy issues for beginners to fix so that they could get familiar with the MMTk project. Eventually, two students were selected by OSPP’s automated matching algorithm, and I mentored one of them to do the project related to JikesRVM and weak references.

Mr. Haohang Shi, the student I mentored, demonstrated his ability to learn things quickly. I simply told him to look at our continuous integration (CI) scripts, and told him that JikesRVM needs a 32-bit toolchain and an old version of JVM (version 8), and that I used LXC to make an isolate environment. In just one week or two, he managed to compile JikesRVM with the MMTk binding in a Docker container in one command. Haohang was surprised that I labelled such a simple project of implementing a new API as an ‘advanced’ task. The JikesRVM is an exotic meta-circular VM, with unconventional semantic extensions to Java in the form of VMMagic, and it interacts with native C and Rust code in unconventional ways different from the JNI which most Java programmers are familiar with. It is also a bit aged, requiring legacy toolchains, and is hard to debug when segmentation fault happens. All of these made his life harder than usual, but he fought through all those difficulties.

From then on, we had an online meeting every week. I basically point him to interesting places in the code base, outlining what should be done, and answering his questions.

Things went on mostly well, until Haohang got stuck trying to call a Rust closure from JikesRVM. I thought that was easy (but I was wrong). The crux was specialising a top-level function with type argument, and passing the pointer to the closure object between Rust and native code. We have similar code in our VM binding repos including the JikesRVM binding, because it is a common task for interfacing with native code. If this happens to my colleagues in the core team, I will just write part of the code for them should they encounter something difficult to implement. However, I didn’t do that for Haohang. One reason was that the rules of OSPP forbid mentors from doing coding for the students (otherwise some mentors would do everything for the student and the student would just sit there and do nothing and still get the bonus). Another reason was that I didn’t want to spoil all the fun of finding the solution by oneself. He eventually figured it out by himself after several weeks. That was a bit long, but he managed to finish the rest of the work before the deadline and his code was eventually merged.

In hindsight, I felt I might have been too harsh for Haohang. After he finished his project, a colleague in the MMTk team asked me a similar question about another binding. Then I realised it may not be so obvious for first-time contributors like Haohang.

Meanwhile, good news came from the other student working on the ARMv8 port. The student was able to run DaCapo Benchmarks on an ARMv8 device with MMTk and OpenJDK. In the end, both student projects were successful. We acknowledged their contributions on our website.

The bad

While the student projects went on well, the organisation of the OSPP’2023 event was far from perfect, and the experience as a participant was, to be honest, far from satisfactory.

The poorly engineered website

The official website was poorly engineered. It forced each user to have exactly one role. But since I am both a community representative and a student project mentor, I had to log in with two different email addresses for two different roles.

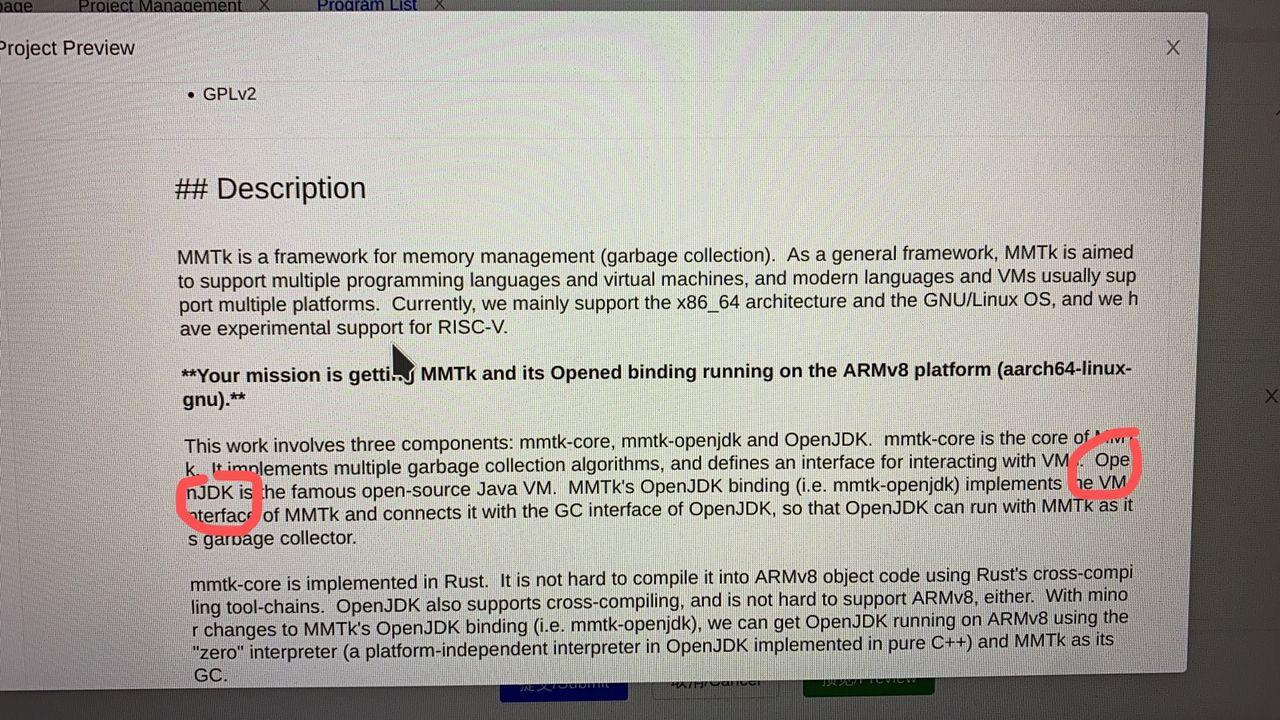

Although OSPP’2023 allowed communities to use Chinese or English or both, the website didn’t seem to be considerate enough for English users. The registration forms limit the length of some fields (such as the project description) by the number of characters, making them unfair for English which tend to have much more characters than Chinese. The typesetting was also weird. When breaking long lines, words can be broken anywhere, disregarding any hyphenation rules of the English language. Look at the following screenshot:

What is ‘Ope’ and what is ‘nJDK’? And it broke ‘support’ into ‘sup’ and ‘port’, and ‘minor’ into ‘mino’ and ‘r’.

It ended up that someone set the CSS property word-break: break-all;. I still

don’t understand why anyone would do that, but I bet nobody tested the web page

with a proper English article and, if anyone actually did, the tester was not

aware of hyphenation rules. Anyway, I reported the issue to the organisers and

they fixed it.

Where did they publish our video?

In the last section, I mentioned that we made an introduction video. Despite of the efforts we made creating it, I didn’t find the video published anywhere by OSPP’2023, and I didn’t get any reply saying whether our video was accepted or rejected.

They prefer WeChat, a proprietary instant messaging app

The official method for communicating with the organisers was via email. But when I sent an email asking questions, one organiser invited me to join a WeChat group. Despite its popularity in China, WeChat is a proprietary instant messaging application mainly focusing on smart phone, and is terrible to use on desktop computers. I felt very strange because OSPP stood for ‘Open Source Promotion Plan’. It was supposed to promote free open-source software. Why do they invite me to use a proprietary application?

But I joined the WeChat group anyway to see what would follow. That was a group titled ‘OSPP community collaboration’, and its members included 400+ representatives from different communities. People were asking questions and pointing out issues about the event, while the organisers replied.

They use proprietary storage service and proprietary image formats

After a few days, the organiser published a template pack for communities to make their promotional ‘posters’. Here is a sample:

For those who don’t know, those who use WeChat or other Chinese social media such as Weibo for promotion usually make such one-picture posters and publish them as tweets, or send them to group-chat channels. The advantage is obvious. It is just so simple, and it bypasses any text-formatting functionalities WeChat or other instant message / social media apps provide to their users, which are often hard to use.

The problem was, the organiser provided the template pack using a link to Baidu Wangpan, a Chinese cloud storage service that requires a proprietary client to use.

Seriously? Was OSPP trying to promote open-source software by forcing participants to use proprietary software? After complaining to the organisers of OSPP’2023, they moved the poster templates to a GitHub repository.

I browsed the repository. They provided the posters in two formats: a .sketch

file and a .figma file. The former was for Sketch, a proprietary graphics

software exclusive to Mac; and the latter was for Figma, a proprietary

web-based graphics software. There were samples in .pdf and .jpg, too.

Are you kidding me? Providing open-source promotion material in two proprietary formats?

I complained to the organisers that there was absolutely no way for Linux users

to open the .sketch file, and I don’t want to register a free account to use

Figma with limited functionality, and I won’t buy a Mac just for OSPP. Even

.psd could be slightly better because GIMP and Krita could open a subset of

.psd files. An organiser replied in an embarrassed tone, saying that the

artist who designed that poster was just asking them whether they should give

the organisers the .psd file, too.

From the conversation, it was obvious that the OSPP organisers hired an artist to make a poster template for OSPP. The artist was probably an average artist who knew nothing about free open-source software, and the artist used their familiar tool, which happened to be Adobe Photoshop, to do their job. The organisers of OSPP probably assumed that community representatives were artists or other non-technical social media operators and probably used Mac, and exported the templates in Mac-friendly formats.

The Open-source Promotion Plan was not promoting open-source the right way

The organisers of OSPP were not organising an event for the free software community, but an average event whose theme happened to be about free software.

Using free software is such a basic thing for organising an event for the free software community. There are many free and open-source communication platforms, such as Zulip which MMTk is using, as well as the good old IRC and mailing lists. There are storage services accessible using only free software, such as their official website. And there is free graphics software, such as GIMP and Krita for bitmaps, and Inkscape for vector graphics.

And there are artists who are also free software lovers. The Krita community hosted interviews with artists who use Krita as their main creative tool. If you need help from artists who love free software, you can just ask, because the free software community is all about creation and sharing. The KDE community held a Plasma 6 Wallpaper Context, with requirements including ‘releasing under the CC-BY-SA-4.0 license’ and ‘creating the wallpaper in a non-proprietary format’. Many artists submitted their work, and the KDE community eventually got a good-looking new default wallpaper for KDE 6, as shown below (taken from their official announcement of the KDE 6 MegaRelease).

It was sad because it was so easy to do it right. Just export the image to the SVG format and all Linux users could edit the image using Inkscape. It should take a sophisticated artist less than ten minutes to do this, and a Linux user to test if it works by opening the SVG image with Inkscape. But they did not do it!

It was also sad because it had been three previous OSPP events and the organisers were still yet to understand the nature of the free software community. I wonder why nobody from the 400+ communities complained about similar issues before.

Organising a free software event this way sent a very bad message to the public that they didn’t really care about software freedom. Ironically, OpenEuler, a domestic Linux distribution, was a co-organiser of OSPP’2023. Using free image formats would have helped OpenEuler demonstrate that their operating system was suitable for everyday use, but they didn’t. I couldn’t help visualising an OpenEuler user going nuts when they couldn’t use their own operating system to open an image file from their own event.

In the end, we didn’t use their poster templates because a Markdown-formatted post in our Zulip channel was just enough for promotional purpose, and we didn’t have a social media account. I’d rather spend one afternoon fixing some bugs than trying to edit PDF or JPEG files directly, which would result in bad-looking images anyway. I raised an issue, asking the organisers to provide materials in free formats. However, at the time of writing, nobody had replied to that issue.

The ugly

Although the organisers of OSPP’2023 didn’t do a perfect job organising the event, they promised to do it better next time. I think there is still hope. Given enough time, OSPP will eventually be organised in the right way.

However, there was still one thing that could be worse — the communities. Not all communities, of course. Only a few of them.

An interesting fact was, although students were required to be enrolled in universities (not written on their official website, but I confirmed with the organisers), there was no such requirement for communities (any communities using OSI-approved open-source licenses would qualify). No offence to the people who didn’t go to university and still made excellent free software, such as Brian Fox who dropped out of high school and made the famous Bash shell. But that rule meant that you had to expect participating communities of any quality, from bleeding edge research projects from the China Academy of Science to hello-world projects made by first-time programmers, and their members to be any kind of people you may possibly meet in streets or psychiatric hospitals (I will elaborate, but no offence to the patients who are actually suffering from mental disorders).

They gave stars to each other’s repos

When I was invited into the WeChat group of 400+ community representatives, I found some members were greeting each other and offering to give stars to each other’s GitHub repositories. One of them ‘kindly’ asked if he could give a star to MMTk’s GitHub repository. I didn’t thank him, but I replied that he needed a five-star rating system for GitHub so that he could give one star to every repo he barely knew, and five stars to the repos he honestly loved.

I consider it cheating to blindly give stars to repositories of one’s ‘friends’ for boosting their ‘reputation’. That would make stars meaningless. In that way, a repo with lots of stars would mean many people genuinely liked it, or merely mean the author had many ‘friends’. I still prefer that stars mean the former.

They wanted everyone to know their software… err… sucks

While organisers and community representatives were using the WeChat group as a Q/A channel, several communities spammed the channel with news about every single point release of their software. Those posts became dominant since July when the programming phase started and very few questions were asked about administrivia. That was annoying.

Well, since they dared spamming, I dared challenging them.

They said they were faster than Spring…

I looked at one project. It advertised as a web framework, with Spring-like IoC container and annotation-based URL routing, but also supported GraalVM and claimed to be many times faster than Spring. Web, IoC and Graal. Didn’t that sound familiar? Yes. Micronaut. That is a Web framework, with Spring-like IoC container, annotation-based URL routing, and GraalVM support, too. I heard about Micronaut about four or five years ago, but this project seemed to be recently started, and poorly documented.

I asked its representative how his project was different from Micronaut.

‘The author of our project has never heard of Micronaut’, he answered, embarrassed, ‘If I have to find any difference, it’s that our project is made in China.’

Their official web site compared their framework against Spring all the time and claimed to be much faster, but never mentioned Micronaut at all. That was not good. You simply can’t claim your project is fast without comparing against the main contenders.

They said they were faster than Netty…

Then another project spammed, and I looked at that, too. It was a simple socket abstraction layer written in Java, similar to Netty, but poorly documented, and claimed to be twice as fast as Netty. I looked at the code for a moment and found something like this:

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

And in another function:

try {

someNetworkOperation(...);

} catch (Throwable e) {

setState(...);

someNetworkOperation(...); // Exception thrown on this line won't be caught.

} finally {

handleNetworkOperationResult(...); // Hey! The network operation may have failed!

}

That didn’t look very professional, did it? Anyone who has learned Java for a

few months knows that e.printStackTrace() is not the right way to handle

errors, and retrying a failed operation doesn’t guarantee that it will be

successful the second time. Omitting all the error-handling code and running

micro benchmarks that always succeed will always give you good numbers, but

that’s meaningless.

I told its representative that they shouldn’t claim they were faster than Netty while they were not doing exception handling properly, just like MMTk can’t claim a GC algorithm to be faster while the write barrier was deliberately turned off. Otherwise people would challenge the result.

‘Our project has been challenged all along’, replied the project representative, ‘and I have long been used to it. Only those who used our project know how pleasant it is.’

Yuck! What an irresponsible developer!

But people were speaking for him!

Strangely, some other people in the WeChat group started to speak for him.

- One person said, ‘Some people want security while others want convenience. Everyone will get what they love.’

- Another person said, ‘As a low-level employee, I can’t care less about how users feel. Only the CTO needs to care about users, and we programmers only need to please ourselves.’

Seriously? I couldn’t believe what I saw. I asked whether they care about downstream projects built upon theirs (such as the ‘Chinese Micronaut’ mentioned earlier which happens to be its downstream project), and apparently they didn’t. Knowing this, I stopped arguing because that would be futile.

They hated free software and didn’t want to promote it

After I complained about OSPP’2023 not providing poster templates in free formats, the organisers said they will be more considerate the next time. However, other people in the WeChat group started whining.

- One person said in some fields, free software were far worse than their proprietary counterparts, therefore we (OSPP) may use proprietary software.

- Another person said it was good to practice the spirits of free software in this event, but we don’t need to force it.

- Another person said that OSPP gave me money and I should be satisfied and shut up.

But let’s look at the poster sample again.

Does it look good? Yes. It does. Well, it is good enough as a poster for an event like OSPP, but not that good. I still don’t quite like blue on blue, or white on light blue. It is not the case that it is so good, with all sorts of fancy effects, that it has to be drawn using best-of-breed tools like Adobe Photoshop. Could anyone create a poster of similar quality (or even better) using only free software? Given the result of the wallpaper contest, the answer is obviously yes. So the right question is not whether we should force using free software, but why not. OSPP stands open-source promotion plan, and the use of free software should be the default, the common sense, rather than something that needs to be ‘forced’.

They learned English for nine years and still couldn’t read simple English articles.

And when I shared the interviews with Krita artists, someone said he couldn’t understand those interviews because he didn’t speak English well.

Seriously? I started learning English since the fourth year in primary school, and nowadays Chinese schools start teaching English as a compulsory course since the third year. By the time when students finish high school, they will have been learning English for at least nine years (unless they were older than me and received worse education in their childhood). How could anyone learn English for such a long time and still can’t understand simple articles like those?

And they hated me.

And someone mentioned me in the group chat, telling me he bought a Mac, a very expensive model, for opening proprietary image formats. I started to realise that someone already started to hate me since I complained about all those proprietary formats and irresponsible developers.

I told him that he could have donated the money to support three students. He apparently broke down mentally, and started telling a pathetic story about himself, including dropping out of high school, joining an open-source organisation, and making 5000+ commits per year which most people don’t believe. Well, I believed what this poor guy said because he supplied a screenshot. But I felt sorry for his organisation because 5000+ commits per year means on average less than 20 minutes for each commit. You can achieve 5000+ commits per year, too, if you make 5000+ trivial changes that take less than 20 minutes to do, and the organisation enforces no code reviewing and no CI tests. You can’t do the same for the MMTk project because all pull requests need to be peer-reviewed and go through comprehensive CI tests which take about an hour, while performance-sensitive changes need to undergo performance evaluation on specially tuned testing machine which takes hours if not days.

Strangely, several other people started to sympathise with him.

- One said he didn’t have a high degree and had a hard time finding a job.

- Another said he only got 28 points (out of 150) in his English exam, and he could have gone to Peking University if he got 100 points or more.

And they swore to support each other.

How weird! I know dropping out of high school does not prevent Brian Fox from becoming a Hero in a Bash Shell, but I never expected I was surrounded by so many ‘heroes’.

A friend of mine

Later that year, a friend of mine visited me in Beijing after living overseas for many years.

He told me that many companies in China were simply copying the business models of companies overseas, but most of them had no idea what they were doing, and will bankrupt quickly. That meant if anyone or any company was doing honest research and development work, they will already be better than 90% of their peers in China.

Wait! That sounded horribly familiar! I told my friend about my experience in OSPP. I also mentioned a recent news about CEC-IDE (see this). CEC-IDE claimed to be an IDE fully original and fully made-in-China. But it ended up that they took the source code of Visual Studio Code, changed its name, added a login window for paid ‘VIP’ services, added some plug-ins, and labelled it as a home-brewed software, an ‘independently software developed by a state-owned corporation, with trustworthy quality’ (and it was close-sourced). Ironically, CEC-IDE was on the CCTV (China Central Television) News when it was released, not long before it became the laughing stock of all Chinese netizens.

It was said that the government already invested hundreds of millions of CNY into the project.

The whole story

Everything suddenly became clear. Here is the whole story, in four parts:

- Since the trade war started, both Chinese companies and the Chinese government worried about their software supply chains.

- They started pouring money into the field of domestic software and open-source software, thinking they could be the rescue.

- Then some developers saw this as an opportunity. Since the consumers wanted domestic and open-source software, they just make domestic and open-source software for them.

Note that those developers don’t have to be FOSS lovers. Anyone who wants some quick money from investors may come, regardless of whether they like free software, whether they worked with free software projects before, or whether they use free software in their work. That explains why someone don’t care about whether we use free software in an open-source promotion plan. And those who speak for them were probably on the same boat.

But it is difficult to start from scratch, especially for those who have never been free software contributor. And here comes part four:

- Instead, they simply copied existing open-source projects and label them as domestically developed.

Some copycats simply took the source code and changed the name. Other more sophisticated copycats wrote code from scratch, using existing open-source projects as frames of reference. Of course they didn’t care about the user, the documentation or the code quality. As long as it was made-in-China and/or open-source, investors would throw money into it, and average people (especially extreme nationalists) would hail it as the future star of China when they saw it on the news. And their bosses probably care more about the number of stars of their repositories because that would attract more eyeballs and probably more investment. And fluency in English was not required as long as they do everything domestically. In fact, some netizens (again especially extreme nationalists) have been advocating abolishing English education in China (although the Chinese education authorities strongly opposed), giving them yet another excuse to fail in their English exams.

Therefore, from time to time, we find Chinese open-source projects that are so similar to world-famous ones, but claim to be domestically developed.

The consequence

A ‘software supply chain’ built this way will be brittle, if working at all. High-level applications will be built on flawed low-level libraries which don’t even handle exceptions properly and may break at any time. But will low-level developers care? Probably not. The decision of which library to use would be way above their pay grade, and they would worry about their house rent and mortgage much more than software quality. Their bosses won’t worry about software quality, either, if their companies monopolise a field, for example, food ordering. When the end users have to choose between one faulty software and another because there are no other choices, all they can do is pressing the reload button and pray it would work the next time.

And will we win the trade war this way? Well, I won’t call it a win if average people are oppressed by faulty software instead of foreign countries.

What about English skills? Well, when they can’t fix their faulty software and realise they can’t read English, they will beg linguists to translate the README files of proper free software projects, while linguists ask them to wait in queue because they are busy translating README files for their rival companies. I’m sure the Chinese education authorities won’t let this happen.

Summary

OSPP’2023 was awesome.

Students were smart and passionate.

The organisers tried hard keeping the event running, but there were much room for improvement.

The communities? Most of them were honestly doing free software developments, while some people were completely jerks.

So should I tell people the Australian National University is awesome, and our research group is doing interesting researches? Yes, to the students, and probably most community members, too. In fact, some students already expressed their interests in studying in the ANU when I told them about this possibility.

What about those who can’t even read simple English articles and those who make bogus claims about their software performance? ‘They are not our target audience’, said one of my colleagues. The ANU does have English language requirements and severe punishment against academic dishonesty.

tags: mmtk - ospp